The Pere Marquette 18 shipwreck lies deep under the waters of Lake Michigan. At that depth, even the clear water of the lake blocks out the light. Even with coordinates, at 500 deep it can be a challenge to get an ROV down there and on target. This is a ship I have wanted to see since it was discovered a few years ago. I was out here in 2022, hovering over the right spot. But with the currents, the ROV drifted off and I wasn’t able to locate the ship. This time would be different.

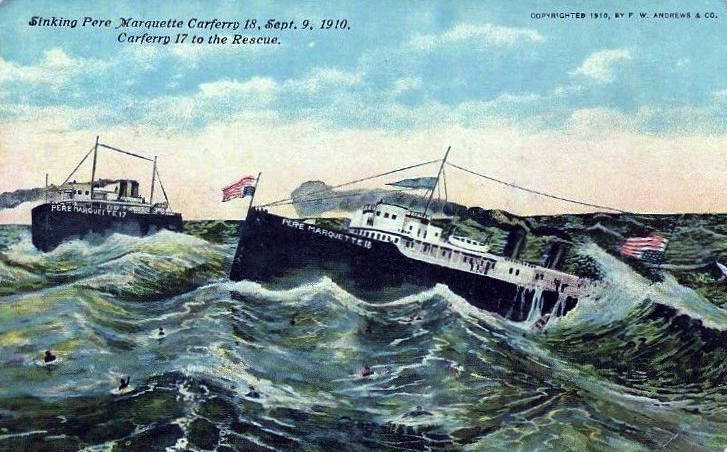

The P.M.18 was a railroad ferry which sank on September 9, 1910. It had departed from Ludington, MI and was heading west. She carried 29 railcars, some cargo, and a few passengers. In the night, it was discovered that the ship was taking on water. The captain tried to make a run for Sheboygan, WI, but the leaking ship filled too fast.

She finally radioed for help, which did arrive. However, before a rescue could get started, the ship went down by the stern, raising up the bow. As it slid beneath the waves, there was a mighty explosion. This was due to air pressure in the hull or water finding her steam engines. Survivors said they saw large pieces of the ship and a number of people being thrown into the air. Undoubtedly, this contributed to the amount people who did not survive.

A lot of mystery surrounded this sinking. None of the higher-ranking officers survived, leaving no accounts from the command crew. Stories of crew members and passengers who survived give us some idea of what happened. Yet, today, it’s impossible to understand the exact cause.

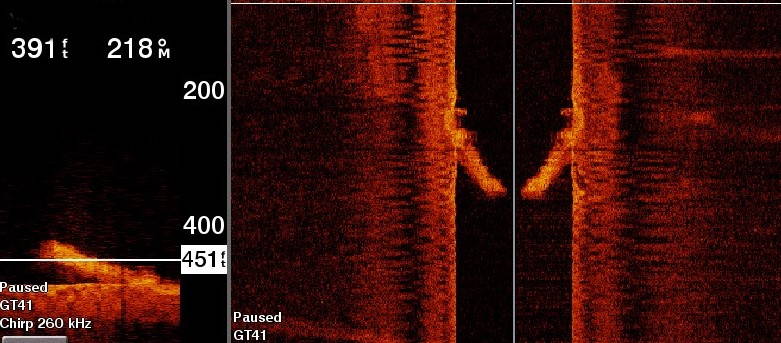

I knew what I was looking for. This shipwreck had been discovered in July 2020 by Jerry Eliason and Ken Merryman from Minnesota. The Pere Marquette 18 rests about 21 miles off of the Wisconsin shore in Lake Michigan, nearly 500 feet deep. Using sonar they discovered it was sticking out of the mud at about a 30-degree angle. They were also the first to get images of the ship, using a drop camera.

Often, it’s left up to individual divers to rediscover a newly found shipwreck. This time Ken and Jerry had given me the coordinates. He said they had done everything that they could with their drop camera system in 2020 but he was familiar with my work and thought I could do it justice.

Filming the Pere Marquette 18

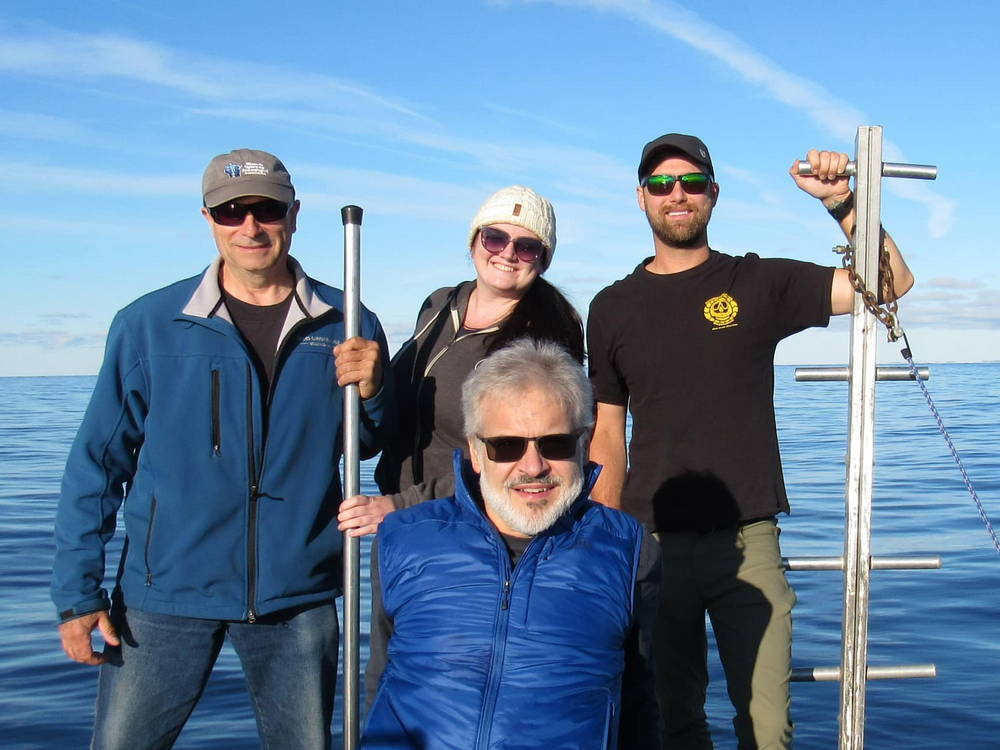

I had come out here to film it, as documenting and sharing shipwrecks with the world is why I’ve created Blueyes Below. This is often a team effort, and on this day, three people were on this expedition with me. The first was Bob Jaeck, an experienced diver and shipwreck explorer. He was helping to document our trip and manage the ROV tether. This allows me to safely control it at depth without having my focus divided by tasks.

Brendon Baillod was also with us. He is one of the leading Great Lakes maritime historians. He had helped with the research that contributed to the initial discovery and was also really interested in getting another look at the wreck.

Since this was a significant ship in an underwater preserve, I had gotten permits from the State of Wisconsin. This led to Caitlin Zant being the fourth member of the crew that day. She is a marine archeologist, who at the time worked for the State of Wisconsin. She was interested in seeing the ship firsthand to get an idea of its condition. She also wanted to determine how much the wreck may have changed since its discovery.

Like last year, I was using my i-Pilot which is often used by fishermen. What it does is keeps the boat stationary with the use of GPS in the head of the trolling motor. I also have an additional GPS unit on the boat about 10 feet away. It knows the position of the boat at all times and based on the two GPS units, keeps the boat incredibly still and locked over my target.

Knowing that the ROV would drift again, I needed something for it to follow to the bottom, just in case there were currents under the water. I had 500 feet of bright yellow line with 30 pounds of anchors that I dropped over the side of the boat and all the way down to the wreck. Once I was on the bottom, I pulled the line up about five feet so it would hang straight and true. This gave me a visual reference for the ROV to follow down, for the seven to nine minutes, it takes for the descent.

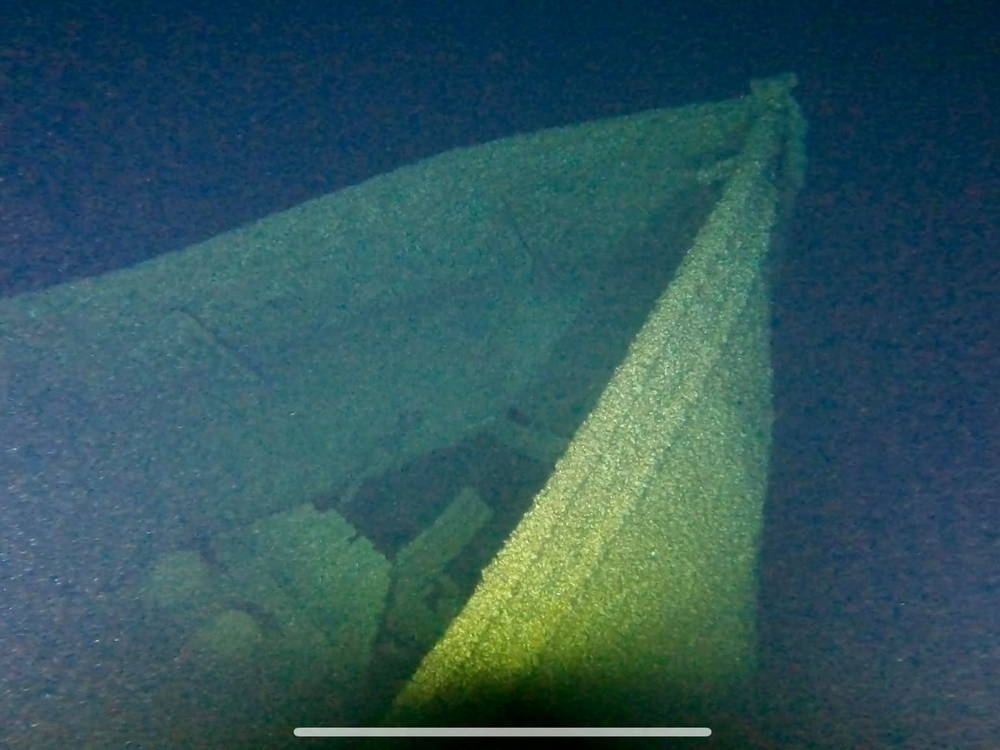

I had two strobe lights on the line. One was positioned just above my anchors and the other one was 20 feet up from that. The first thing I saw was my strobe lights in the darkness. Then, as I got down towards the bottom my lights actually illuminated the bottom of the lake. I didn’t see the Pere Marquette 18 at that point. So, when I got to the bottom I stopped descending. I looked slowly to the right, looking for potential entanglements because I didn’t know at that point where I was. No shipwreck there. Then I slowly looked to the left. Five feet from me is the starboard side of the pier Marquette 18, speared into the lake bottom.

I had come down right where it starts entering the mud. It’s buried quite deep in the bottom of the lake and rises up at a severe 30-degree angle. Brendon Baillod thought that when it hit, the ship went so far into the mud it hit bedrock. The waves and undulation of the surrounding lake bed are just utter chaos. It looks like a shockwave went out and Brendon thinks that’s from the back of the vessel hitting bedrock because it came down so hard.

As I began to explore the wreck, I had to be careful. I had been warned several times by Brendon that there were a lot of entanglements on the wreck. A lot of the lifeboat davits are still on the ship and they look a bit like candy canes but are definitely dangerous for ROV tethers. There was also a lot of twisted metal and collapsed structures.

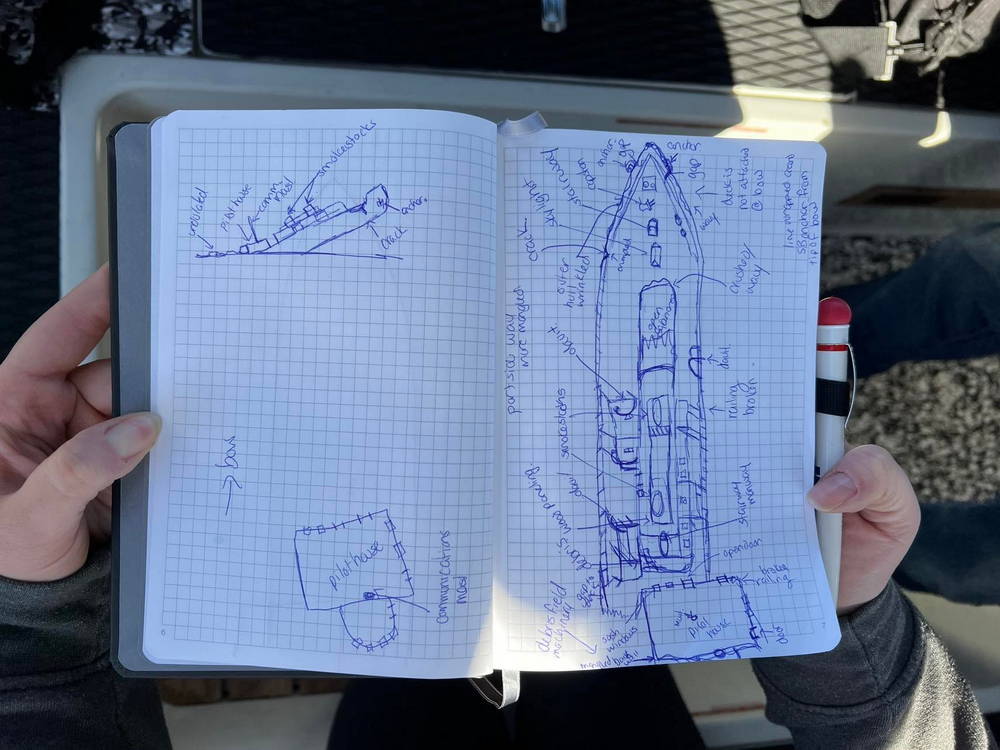

I had to be careful and slow with the movements to avoid getting the tether of the ROV tangled. Since there’s no public video of this, I was essentially going in blind. As I worked my way around the wreck, I was essentially imagining it in my mind. I noted where the hazards were and what the layout was.

At the same time, Caitlin was watching the video monitors and doing a site sketch. She was also telling us what things were because she’s very familiar with the layout of these types of vessels. It’s such a jumbled mess down there. It’s hard for someone like me who isn’t familiar with shipbuilding to understand what I’m looking at.

Caitlyn was able to identify objects and structures as we worked our way around the wreck. She sketched it, which gave us a good overview. It’s so dark down there that it’s hard to see more than 10 or 15 feet at a time.

We ended up taking the ROV over most of the wreck, from the bow down to where the ship disappeared into the mud. We were able to get a lot of clear video footage and a number of very clear stills to document the condition of this wreck. We were able to spot some of the ship’s machinery and identify the pilot house, which was no longer at the front of the superstructure. In the end, we gave a copy of the footage to Caitlyn for the archeologists to use in their write-up.

In total, it was only about a 4-hour expedition on the water. Having the coordinates certainly helps. Also, my experience from the previous year meant we had a good plan once we arrived on-site. Finding the wreck, hovering, and getting the ROV down and up was a very smoother operation which let us focus on the footage.

We finished this with a great feeling of accomplishment, and once safely back on shore, we all went out to eat and reviewed the footage, this time on a computer where it was easier to see. It was good to work with a team, and each person played a unique role. At 500 feet down, I had finally seen the Pere Marquette 18.

0 Comments