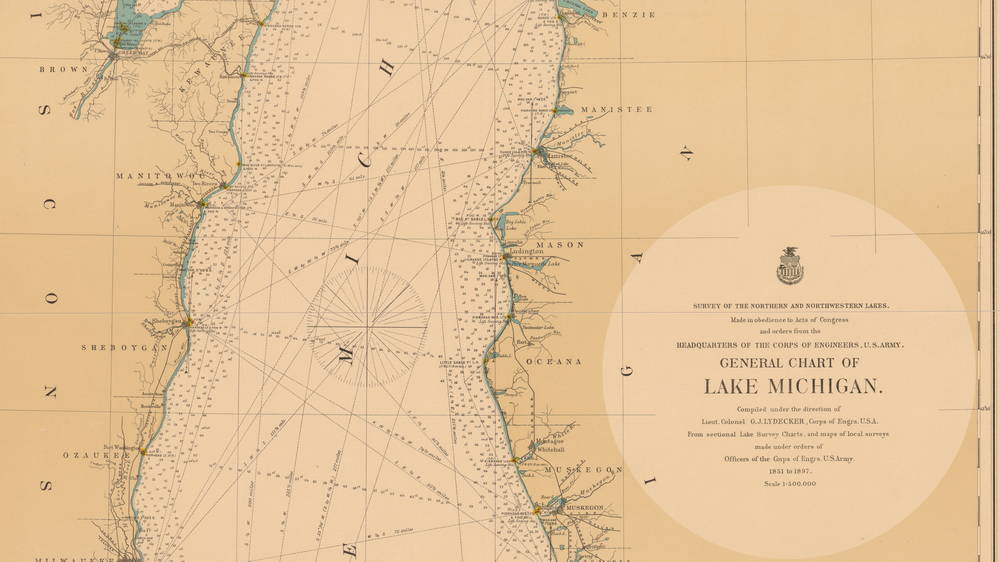

Since the 1600s, the Great Lakes have been a link between North America and Europe. The French, English and Spanish all claimed various parts of the lakes at one point or another. Exploration moved westward, and in its wake followed settlement that grew into commerce. Lake Michigan, the westernmost, played a vital role. It was the supply line for pioneers to the west and large commercial interests to the east. This movement across the water would lead to a large number of shipwrecks in Lake Michigan.

Estimates of the number of shipwrecks in the Great Lakes range from 6,000 to 10,000. Lake Michigan could be home to well over 1000 of them. The first European ship to sail the lake, The Le Griffion, also became the first shipwreck in 1679. It would not be the last.

Part of an inland sea

By the definition of “sea,” the great lakes are still only lakes. But they are huge. They hold nearly ⅕ of all the world’s unfrozen fresh water. They are deep, too, with depths beyond 1200 feet, depending on the lake. All told, they have a shoreline that spans over 10,000 miles. The size is mind-boggling. Of the five lakes, Lake Michigan is second in almost every measure of size.

A feature of the Lakes is that they are large enough to allow storms to build massive waves. Lake Michigan is capable of creating 25-foot waves when the conditions are right. While this seems high, ships in the 18th century were built to withstand them. In fact, they often faced larger ones in the open ocean.

What makes Great Lakes waves deadly is that they are large, but they are also “narrow.” In Lake Michigan, waves tend to be steeper and closer together than what is found in the ocean. This means that there is a lot less time and space for ships to ride the waves. This can create two serious problems.

When ships take the waves head-on, it’s possible to have both the stern and the bow suspended on peaks. This leaves the center of the ship hanging, unsupported, over the trough. Ships are not built to withstand this sort of stress, and the keel can crack, breaking the ship in two. The other dangerous situation arises when ships can’t take the waves head-on. If they lose the ability to control the direction of the ship, they may end up sideways. As the waves begin to crash over the deck, the wind will begin to push it over. Each wave can tip the ship farther, and with not enough time to right itself, the outcome is usually deadly.

Early technology contributes to shipwrecks in Lake Michigan.

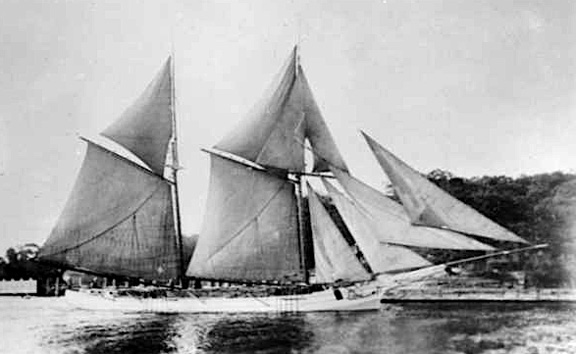

The earliest ships to cross the lake were wooden sailing vessels. By the 1800’s the “schooner” was the most popular type of ship. They were anywhere from 40 feet to over 200 feet long, had flat bottoms, and had two to four masts. They were ideal for entry into the shallow ports along the coastlines of the Great Lakes. The majority of shipwrecks in Lake Michigan are schooners.

There isn’t any design flaw that made these ships particularly dangerous. They were state-of-the-art designs for that time. But the wood construction made them more susceptible to damage and fire. Wood is strong, and it is buoyant but isn’t as rigid as steel. A ship, caught in a storm could lose sails, rigging and even its masts. Fires could start if a cooking stove was knocked over. At that point, it would be at the mercy of the winds and the waves with an outcome that usually wasn’t good.

Eventually, steamships began to replace the schooners. Initially, they were of wood construction, too. But, they had an advantage. Steamers could take any direction they wished because they were steam-driven. Their movement was not determined by the wind. The ship’s boiler, which produced steam, was usually coal-fired although early steamers burnt tons of wood for fuel. As long as the fire was burning to create steam, the ship would have power.

But, the threat of fire became much more prevalent. Embers from the smokestack could land in the cargo. If this wasn’t discovered in time, the ship could catch fire and burn to the water line. Boilers, too, were new technology. They were known to explode on occasion, ripping the ship apart.

As boilers became safer and more reliable, shipbuilders also turned to iron and steel. It was strong, rigid, and could better withstand the elements. These early metals were not entirely understood by shipbuilders of the time. Some ships cracked and split along seams when caught in rough seas. Also, propeller shafts passed through the hull. When one broke and fell to the bottom, the lake water would come pouring into the ship.

Too much traffic

There were hundreds of ships plying the waters of the Great Lakes during the 1800s. Radar, which is common on even small pleasure craft today, wasn’t even being thought about yet. Radio, too, was brand new. Most information travelled by mail or along telegraph lines. With so many ships going to and fro, there were bound to be accidents.

There wasn’t much ability to predict the weather. Sailors would learn to read the skies and feel the winds, but that was often a very inaccurate guess of what was to come. If rough weather was coming in, or already upon a ship, they would often try to head for shelter. On northern Lake Michigan, the east side of the Manitou Islands was a popular place to ride out storms. But, it could be dangerous to get there if the ship was already caught in bad weather.

The waters on the open lakes were the most dangerous. Shipping lanes developed that followed the coastlines, about 10 miles offshore. Today, those lanes are split into upbound and downbound. Depending on which way the ship is headed, they are expected to be on a particular side of the shipping lane. Unfortunately, this law wasn’t put into place until the early 1900s.

Ships would hug the shoreline and when visibility got bad, they could collide. Sailing through the pitch darkness of a stormy night increased the likelihood of a collision considerably. These incidents weren’t always head-on. At times, faster-moving ships would run over slower-moving ones in bad conditions, too.

Captains also had a choice. They could profit and time first, and sail directly to their chosen ports. Chicago and Milwaukee were common destinations. However, if a storm or a mechanical issue were to strike mid-lake, away from the shipping lanes, saving the ship and rescuing the crew was not likely.

It is a lot safer today

Shipwrecks are incredibly rare today. One of the last to happen in Lake Michigan was the Fransisco Morazan. She ran aground off S. Manitou Island in 1960. Once stranded, the waves have battered and broke her. Today, a lot of her superstructure is still above the water. In fact, from Sleeping Bear overlook, a person with keen eyes (and binoculars) can still see the shipwreck.

Time and technology have moved on, and shipping has become a lot safer on Lake Michigan. Ships today are purpose-built to handle the rigors of bad weather and high seas on the Great Lakes. Radar, weather forecasting, GPS, and radio all had a profound impact on safety as well.

There are also far fewer cargo ships and with the exception of Lake Express and S.S. Badger, no regular passenger service across the waters. This cuts down the likelihood of collisions immensely.

Yet, the lakes are not to be underestimated and they are not tamed. Shipping companies take the threat of disaster seriously. They work hard to protect their employees and their investments. There are still plenty of shipwrecks in Lake Michigan to find, no one is looking to add any more.

0 Comments